- Home

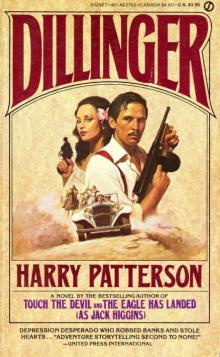

- Dillinger [lit]

Jack Higgins - Dillinger Page 8

Jack Higgins - Dillinger Read online

Page 8

They climbed down and Rivera said, "I've had enough of this damned heat. I'll go out to the hacienda in the cool of the evening."

Rivera preceded them inside.

Fallon said to Dillinger, "I hope he doesn't run into Rose first thing. They hate each other's guts.

"Come on," Dillinger said, "I need to wet my whistle."

Inside there was no sign of Rivera. Fallon led the way into a large stone-flagged room. There were tables and chairs and a zinc-topped bar in one corner, bottles ranged behind it on wooden shelves. A young man poured beer into two glasses.

"Lord God Almighty's just been in to tell me you were here. He's gone up to his room," he said in English with a pronounced French accent.

Fallon picked up one of the glasses and emptied it in one long swallow. He sighed with pleasure and wiped his mouth with the back of one hand. "Another like that and I'll begin to feel human again. Andre Chavasse, meet Harry Jordan."

They shook hands, and, grinning, the young Frenchman put two more bottles on the counter. "We heard you were coming, courtesy of Rivera's telegraph. All the comforts of civilization, you see."

Chavasse was perhaps twenty-five, tall and straight with good shoulders, long black hair growing into foxtails at his neck. He had a handsome, even aristocratic face. The face of a scholar that was somehow relieved by the mobile mouth and humorous eyes. A man whom it would be hard to dislike.

Dillinger turned to Fallon. "What happens now?"

Fallon shrugged. "I suppose he'll want us at the mine tomorrow."

"Where do we stay?"

"Not at the hacienda, if that's what you're thinking. Rivera likes to keep the hired help in their place. There's a shack at the mine."

"You're staying here tonight," Chavasse put in. "Rivera booked the room. It's the brown door at the top of the stairs."

Dillinger swallowed his beer and put down the glass. "If it's all right with you, I'll go up now. I feel as if I haven't slept in two days."

Fallon grinned at the Frenchman. "We had ourselves a rough ride in. Villa and his boys tried to take over the train, then we ran into Ortiz on the way. That didn't improve Rivera's temper, I can tell you."

"You saw Ortiz?" Chavasse asked eagerly. "How did he seem?"

Had blood in his eyes, if you ask me. One of these days Rivera's going to do something about him."

"I would not like to be Rivera when that day comes," the Frenchman said gravely.

"You think he's dangerous?" Dillinger asked.

Chavasse took a cigarette from behind his ear and struck a match on the counter. "Let me tell you something, my friend. When you speak of the Apache, you speak of the most dangerous fighting men who ever walked the face of the earth. Rivera will find one day that he has pushed Ortiz once too often."

"And Andre should know," Fallon said. "He's forgotten more about Apaches than I'll ever know."

"Right now," Dillinger said, "the only thing I'm interested in is about eight hours' sleep and whatever passes for a bath around here."

He walked out into the dark hall and paused to remove his jacket, blinking as the sweat ran into his eyes. A step sounded on the porch, and a spur jingled as someone entered.

He turned slowly. A young woman stood in the doorway looking at him, the harsh white light of the street outlining her slim figure. Booted and spurred, she wore Spanish riding breeches in black leather, a white shirt open at the neck, and a Cordoban hat.

But it was her face that blinded him, slightly Oriental eyes that were unusually large, the nose tilted, a sensuous mouth. There was about her a tremendous quality of repose, of tranquility almost, that filled him with a vague irrational excitement.

You are Senor Jordan?" she said. "Harry Jordan, who is to run the mine for my uncle? I am Rose Teresa Consuela de Rivera."

She removed her hat, revealing blue-black hair in braids coiled high on the back of her head. She put out her hand in a strangely boyish gesture, and he held it for a moment, marvelling at its coolness.

"You know, for the first time I actually feel glad I came to Mexico," he said.

The look that appeared on her face lasted for only a second, and then she smiled. Laughter erupted from her throat and the sound of it was like a ship's bell across water.

Seven

It was evening when Dillinger awakened. The coverlet had slipped from him in his sleep, and he lay there naked for a moment, watching the shadows lengthen across the ceiling, before swinging his legs to the floor. The window to the balcony stood open, and the curtains lifted in the slight breeze.

The courtyard at the rear of the hotel seemed deserted when he peered out. He quickly filled the enamel basin on the washstand with lukewarm water from a stone pitcher, went out on to the balcony, and emptied the basin over his head.

He toweled himself briskly, pulled on his pants and shirt, then examined his face in the cracked mirror, running a hand gingerly over the stubble of beard. He opened one of his suitcases, took out razor and soap, and got to work.

There was a knock at the door, and as Dillinger turned, wiping soap from his face, Rivera entered. He carried Dillinger's shoulder holster and the Colt.32. He dropped them on the bed.

"Well, the world is full of surprises," Dillinger said.

"There are eight rounds in there, my friend, as you know. If we have trouble with Ortiz, do you think eight rounds are enough?"

Dillinger twirled the Colt around once by the finger guard. "One round is enough. Eight can be too few. Depends on the circumstances."

"Am I wrong to trust you?"

"You are wrong to trust anybody."

Rivera laughed. "Here are some pesos in case you want to indulge yourself in the saloon downstairs. It is not a gift, but an advance against your pay. Don't lose it at poker."

"I don't lose at poker," Dillinger said, "or anything else. What about gas for my car?"

"I trust you with a gun because I have two, and I have Rojas. But I do not trust you yet with gas, which would give you ideas of leaving Hermosa. Perhaps you will learn to ride a horse, Americano," Rivera said, laughing again as he closed the door behind him.

Somewhere, someone was playing a guitar, and a woman started to sing softly. Dillinger put on the shoulder holster, finished dressing, brushed back his hair, and went outside.

Rose de Rivera leaned against the balcony rail at the far end of the building, her face toward the sunset as she played. In Chicago, he had once heard a woman singing in Spanish in a night spot, but nothing like this. Rose's voice was as pure as crystal.

His step caused her to turn quickly, the sound of the last plucked string echoing on the evening air in a dying fall. She wore a black mantilla and a scarlet shawl was draped across her shoulders. Her dress of black silk was cut square across the neck. A band of Indian embroidery in blue and white edged the bodice.

She smiled. "You feel better for your bath?"

"You saw me?"

"Naturally I turned my back."

"My compliments on the dress. Not what I'd looked for."

"What did you expect, a cheong sam? Something exotically Chinese? I wear those, too, if I'm in the mood, but tonight the Spanish half of me is what I feel."

"Are you more proud of your Chinese half or your Spanish half?"

"When I am feeling Chinese, I am proud to belong to an ancient and wise civilization except for one thing."

"What's that?"

"They invented gunpowder," she said, and she came close. He didn't know what to expect, but all she did was touch his side where the shoulder holster showed. "Who are you?" she said.

"What about your Spanish half?" he said, avoiding the question.

"My father used to tell me a Rivera sailed with the Spanish Armada."

"Didn't they lose against the English?"

"Is winning always everything?"

"The Americans beat the English."

"You are all terrible-vain, proud, impossible. What do you do for a living when

you are not being strong man for my uncle? You know he is only playing you off against Rojas?"

"Yes."

"You know what happened to the last American who worked for him?"

"Yes."

"You think God gives you special protection that others do not have?"

"Yes," he said, laughing.

"You haven't answered anything I've asked you. Why are you being so mysterious?"

Dillinger thought how different she was from the pushovers back home. If he'd seen her in Indiana, he'd have thought of her as a stranger. His girl friend, Billie Frechette, was part Indian, really a dish, but nothing like Rose.

Dillinger kissed Rose lightly, the way he'd seen in the movies, keeping his chest away from her so she wouldn't feel the holster pressing against her. When he'd kissed Billie, she always put her hand down there right away, but Rose just smiled and turned away just enough so he wouldn't try again.

For a second he thought it was his heart beating loudly, but it was a drum pulsating through the dusk. Voices started an irregular chant, the sound of it carrying toward them on the evening breeze. There was a flicker of flame from a hollow about a hundred yards away, and he noticed an encampment.

"Indians?"

"Chiricahua Apaches. They sing their evening prayer to the Sky God asking him to return the sun in the morning. Would you like to visit them? We have time before supper."

A flight of wooden stairs gave access to the courtyard, and they moved out through the great gateway toward the camp. Rose took his arm, and they walked in companionable silence.

After a while she said, "Fallon told me about how my uncle tricked you. He is a hard man."

"That's putting it mildly. How do you and he get on? Your uncle would like to see you go?"

"My presence is a continual irritation. He's offered to buy the hotel many times."

"But you don't want to leave?"

She shook her head. "When I was twelve my father sent me to convent school in Mexico City. I was there for five years. The day I returned, it was as if I had never been away."

"Why should that be?"

"This countryside," she said, "it's special. I don't like cities. Do you?"

"Not too much," he said.

"You are lying to please me."

He wanted to tell her that out in the countryside the banks were far apart and didn't have all that much money lying around. You had to go to the towns and cities for the big loot.

"In Mexico the people make heroes of their bandits. In the States, they make heroes of gangsters."

Was she guessing? Did she know something?

"Your uncle," Dillinger said, "is a bigger bandit than Villa."

"Yes," she said, laughing, and took his hand, but just for a moment. He felt desire again, and hoped it didn't make him crazy in the head the way it used to, the longing he couldn't stand.

"In the countryside here," she said, "have you noticed that the rocks shimmer, the mountains dance, and everything is touched with a blue haze? I think the countryside is like the face of God. Something we are not meant to see too clearly."

Her hand was on his arm, an unmistakable tenderness in her voice. He looked down at her. She flushed, and for a moment her self-assurance seemed to desert her. She smiled shyly, the evening light slanting across her face, and he knew that she was the most beautiful woman he had ever seen.

There was something close to a virginal fear in her eyes, and this time he squeezed her hand. Her smile deepened, and she no longer looked afraid, but completely sure of herself.

Without speaking, they turned and moved on toward the encampment. There were three wickiups, skin tents stretched tightly over a frame of sticks, grouped around a blazing fire. Three or four men crouched beside it singing, one of them beating a drum, while the women prepared the evening meal.

Several children rushed forward when they saw Rose, but then they stopped shyly. She laughed. "They are unsure with strangers."

Rose moved toward them, and the children crowded around, wreathed in smiles. She spoke to them in Apache, then beckoned to Dillinger. "There is someone I want you to meet."

She led the way to the largest wickiup. As they approached, the skin flap was thrown back. The man who emerged looked incredibly frail. He wore buckskin leggings, a breech clout, and a blue flannel shirt, a band of the same material binding the long gray hair.

His face was his outstanding feature. Straight-nosed, thin-lipped, with skin the color of parchment, there was nothing weak here, only strength, intelligence, and understanding. It could have been the face of a saint or a great scholar. By any standards he looked like a remarkable man.

Rose bowed her head formally, then kissed him on each cheek. She turned to Dillinger.

"This is my good friend, Nachita-the last chief of the Chiricahuas.

Dillinger put out his hands in formal greeting and felt them gripped in bands of steel. The old man spoke in surprisingly good English, the sound like a dark wind in the forest at evening.

"You are Jordan, Rivera's new man."

"That's right," Dillinger said.

Nachita kept hold of his hands, and something moved in his eyes like a shadow across the sky. The old man released his grip, and Dillinger turned away, looking out across the camp.

"This is quite a place."

Behind him, Nachita picked up a dead stick and snapped it sharply, simulating the distinctive click of a gun being cocked. Dillinger instinctively reached for the gun under his arm and turned, crouching, the Colt in his hand as if by magic.

Nachita smiled, turned, and went back into his wickiup. His lesson was for Rose. Here was a man who handled guns as if they were his hands.

Dillinger found Rose watching him, her face serious, the firelight flickering across it. He laughed awkwardly and put the gun away.

"Nachita certainly has a sense of humor," Dillinger said.

There was a pause as she looked at him steadily, and then she said, "We must go back to the hotel. Supper will be ready."

Dillinger took her arm as they left the camp. "How old is he?"

"No one can be sure, but he rode with Victorio and Geronimo, that much is certain."

"He must have been a great warrior."

They paused on a little hill beside the ruined adobe wall, and Rose said, "In eighteen eighty one, Old Nana raided into Arizona with fifteen braves. He was then aged eighty. Nachita was one of the braves. In less than two months they covered a thousand miles, defeated the Americans eight times, and returned to Mexico safely, despite the fact that more than a thousand soldiers and hundreds of civilians were after them. That is the kind of warrior Nachita was."

"Yet in the end the Apache were defeated, as they were bound to be."

"To continue fighting when defeat is inevitable, this requires the greatest courage of all," she said simply.

Funny she should say that. He'd imagined himself one day coming into a bank he'd cased, but not well enough, and finding himself in a trap, every teller a G-man waiting with a gun instead of a wad of bills. He'd imagined himself backing out of the bank, shooting machine guns from both hips, knocking out the G-men like ducks in a gallery. He'd walked out of three movies where he could tell that the gangster was going to get killed in the end.

...

After supper Dillinger went into the bar and joined Fallon, who was sitting with Chavasse at a small table in the corner. Fallon produced a pack of cards from his pocket and shuffled them expertly.

"How about joining us for a hand of poker?"

"Suits me." Dillinger pulled forward a chair and grinned at the Frenchman. "Shouldn't you be working?"

Rose arrived, carrying bottles of beer and glasses on a tray. "My manager is permitted to mingle with special guests," she said.

"As always your devoted slave," Chavasse said dramatically, grabbing her hand and kissing it with pretended passion.

She ruffled his hair and disappeared into the kitchen.

Dillinger felt a sting of jealousy. He said, "She just introduced me to old Nachita. Quite a guy."

Chavasse said, "Everything that's best in a great people. He taught me more than anyone else about the Apache."

"Fallon tells me you're quite an expert on the subject."

The Frenchman shrugged. "I studied anthropology at the Sorbonne. I decided to do my field work for my thesis as far away from home as I could get. I meant to stay six months. But where in Paris could I get a job like this?" He laughed. "And such a nice boss."

Jack Higgins - Dillinger

Jack Higgins - Dillinger