- Home

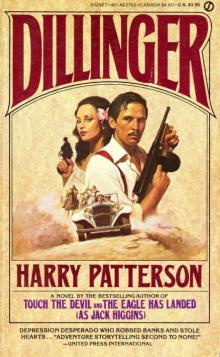

- Dillinger [lit]

Jack Higgins - Dillinger Page 3

Jack Higgins - Dillinger Read online

Page 3

When Dillinger came back, he was carrying a small case that he carried inside and placed on the table. He opened it carefully. Inside, there was a stack of money, each bundle neatly banded in a bank wrapper.

The old man's eyes widened.

"Fifteen grand there, all I have to show for a misspent life," Dillinger smiled. "Keep it for me. If I don't come back, use it any way you see fit."

"No, Johnny, I couldn't," Doc whispered. "God, where are you going?" the old man demanded.

"To see a man about a bank loan," Dillinger said, his back to the old man as he went down the steps to the Ford, got behind the wheel, and drove away.

George Harvey glanced at his watch. It was just after two-thirty, and it occurred to him that an early finish might make sense today. The relentless rain that had cleared the streets of Huntsville hammered ceaselessly against the window of his office and filled him with acute depression. He was about to get up when the door opened and Marion, his secretary, looked in.

"Someone to see you."

Harvey showed his irritation. "I don't have any appointments."

"No, he knows that. A Mr. Jackson of the Chicago and District Land Company. Says he's only in town by chance and wonders if you could spare him a few minutes."

"Does he look like money?"

"I'd say so."

"Okay. Bring him in, give it five minutes, and then come in to remind me I've got another appointment."

She went out and returned a moment later to usher Dillinger in. He held the yellow slicker over one arm, and Marion took it from him.

"I'll hang it up for you."

"That's very kind of you."

She felt an unaccountable thrill as she went out, closing the door behind her, and Dillinger turned to face Harvey.

"It's good of you to see me, Mr. Harvey."

Harvey took in the excellent suit, the conservative tie, the soft-collared shirt in the very latest style, and got to his feet.

"That's what we're here for, Mr. Jackson. Take a seat and tell me what I can do for you. You're in the property business?"

"That's right. Chicago District Land Company. We're in the market for farm properties in this area-suitable farm properties. Our clients, the people we represent in this instance, intend to farm in a much more modern way. To make that pay, they need lots of acreage. Know what I mean?"

"Exactly," Harvey said, opened a box on his desk and offered him a cigar. "I think you'll find you've come to the right place, Mr. Jackson."

"Good." Dillinger took the cigar and leaned forward for a light. Harvey frowned. "You know, I could swear I've met you some place before."

"That could be," Dillinger said. "I get around. But let's get down to business. I need a bank down here."

"No problem."

"Good, then I'd like to make a withdrawal now."

"A withdrawal?" Harvey looked bewildered. "I don't understand."

"Yes," Dillinger said. "Twelve thousand dollars should do it, what with my expenses and all."

"But Mr. Jackson, you can't make a withdrawal when you haven't put anything in yet," Harvey explained patiently.

"Oh, yes I can." Dillinger took a Colt.45 automatic from his pocket and placed it on the table between them.

Harvey's whole face sagged. "Oh, God," he whispered. He looked at the man's face, and it came to him. "You're John Dillinger."

"Pleased to meet you," Dillinger said. "Now we've got that over with, you get twelve grand in here fast, and then you and me will take a little ride together."

Dillinger walked over very close to Harvey so that the banker could feel Dillinger's breath on him.

Harvey was not a religious man. He went to church Sundays because his customers went to church. But he found himself hoping that his Maker was looking down right now to protect him.

"Are you going to kill me?" Harvey asked.

"You're going to kill yourself, Mr. Harvey, if you keep shaking that way."

They both heard the door open. Quickly, Dillinger pulled his gun arm in and turned so that it wouldn't be seen from the door. It was Harvey's secretary, saying "Your next appointment is here, Mr. Harvey."

There was a slight pause. Dillinger waited, and Harvey took a deep breath. "Cancel it. They'll have to come in tomorrow. Tell Mr. Powell I want twelve thousand dollars in here." He glanced at Dillinger. "Will fifties be okay?"

"Just fine," Dillinger said amiably.

The woman went out. Dillinger put the Colt in his right-hand pocket, stood up, and walked around the desk behind Harvey. "You got a briefcase handy?"

"Yes," Harvey said hoarsely.

"When he comes, put the money in that. Then we leave."

The door opened a moment later, and the chief cashier, Sam Powell, entered, carrying a cash tray on which the money was stacked. "You did say twelve thousand, Mr. Harvey?"

"That's right, Sam, just leave it on the desk. I'll clear it tomorrow. He improvised fast. "I'm into a situation that requires instant cash."

"Too good an opportunity to miss," Dillinger put in.

Powell withdrew, and Harvey took his briefcase from under the desk, emptied it, and started to stack the cash inside. He looked up. "Now what?"

"Get your coat," Dillinger said patiently. "It's raining outside or hadn't you noticed? We walk right out the front door and cross the street to the Ford coupe."

"You're going to shoot me?" Harvey said urgently.

"Okay if you make me. If you behave yourself, I'll drop you outside of town. You can have a nice long walk back in the rain to think about it all."

Harvey got his coat from the washroom and put it on. Then he picked up the briefcase and moved to the door. "Now smile," Dillinger said. "Look happy. Here, I'll tell you something funny. You know what guys in your position always say to guys like me in the movies? They say, "You'll never get away with it."

And Harvey, nerves stretched as tight as they would go, started to laugh helplessly, was still laughing when they went out to Marion's office and picked up Dillinger's oilskin slicker and felt hat.

Sitting at the table, the screen door propped open, Doc Floyd heard the car drive up outside. He straightened, glass in one hand, the other on Dillinger's case and waited fearfully. Dillinger appeared in the doorway, the briefcase in one hand. The dog whined and moved to his side, and he reached down to scratch its ears.

He tossed the briefcase on to the table. "Three thousand in there plus a little interest. Twelve thousand in all. That seem fair to you. Doc?"

The old man placed a hand on the briefcase and whispered, "You kill anyone, Johnny?"

"No. I found your friend Harvey a real cooperative fellow. Left him ten miles out of town on a dirt road to walk back in the rain." He unfolded the paper from around a stick of chewing gum. "You can pay what you owe on this dump now, Doc, or take the money and run all the way down to the Florida Keys and that daughter of yours." Dillinger popped the gum into his mouth. "Want some?"

"What about you, Johnny? That fellow Leach..."

"To hell with him."

Doc wrung his hands. Just then they both heard a car in the distance.

"That coming this way?" Dillinger asked.

"Any car you can hear ain't on the main road. Get in the back room, Johnny, quick. Take the briefcase. Take the guns. Anything else around here yours?"

Doc turned clear around, spied the coffee cups, put them in the sink. The only thing he saw in the room that frightened him was the look that came into Dillinger's eyes.

"Please go into the back room. If you shoot it out with someone here, win or lose, I'll never get to see my grandchild in Florida, Johnny. Please?"

Dillinger went into the back room, taking the briefcase and guns. As soon as he slammed the door, Doc rushed out of the house. Thank heaven the rain had stopped, he thought. He wanted to meet the car as far from the house as he could.

He could see it was a Model A, black as they all were, spewing a cloud of dust behind it. The man dr

iving didn't look familiar. Then Doc saw that a woman was sitting beside him.

The man turned the engine off and got out. "Evening," he said.

Doc nodded. He'd seen traps before, man and woman in the front, three men hiding behind the seat.

The man said, "Me and the Mrs. kind of got lost."

"Where you headed?"

"Moline."

"You got a long ways to go."

"Know that. We figured to stop in a hotel someplace tonight. Or thought maybe we could pay someone to stay over."

"You don't want to stay here," Doc said. "My woman has black fever."

The man didn't know what black fever was any more than Doc did, but he took a step backward.

"I can get you some water," Doc said.

"No, thanks," the man said. "We'll be shoving off. When I get to the road, I turn left or right?"

"Left's the only way that'll head you toward Moline. There's a town an hour down the road got rooms above the general store."

"Thank you kindly. You want us to tell the sheriff or anybody to send a doctor for your wife?"

"I'm a doctor."

The man got back into his car. He didn't believe Doc was a doctor any more than he believed in the man in the moon.

"She's dying," Doc said, "and we want to be left alone for what time's left."

"I appreciate that," the man said, got in the car, and drove off slowly so as not to scatter too much dust in Doc's direction. Doc hurried to the house, opened the door of the back room, and said, "It's okay, Johnny. Travelers. Sent them on their way."

"I hate this."

"Hate what, Johnny?"

"Hiding like a rat. I wasn't made for it. I want to walk around like a free man."

"You'll sure be able to do that," Doc said, "soon's the heat's off. Johnny, I'm old enough to be your father. You been real good to me, so I'm going to chance saying something."

He wished Dillinger wasn't looking at him with those stony eyes.

"Say it!"

That man was sure on edge, Doc thought. "You take too many chances. You've got to head south, I don't mean Texas, I mean all the way to Mexico, where they can't catch you, Johnny."

"That means getting across the border."

Doc poured whiskey into a spare glass and pushed it across to him. "Listen, Johnny, a few years back I had dealings with a man who ran people into the country from Mexico illegally. European refugees, people like that."

"So?"

"West of El Paso, there's a small town called Sutter's Well. Used to be a silver mine. It's a ghost town now. The back trail out of that town crosses the Mexican border. No border post, no customs, no police. That's the way we used to bring them in."

"Will it take a car?"

"Oh, sure. Dirt road, but sound enough. You need to carry plenty of spare gas. Six or seven five-gallon cans in the trunk should cover you. Couple of spare fan belts. I can let you have a set of tools. Know your way around an engine, Johnny?"

"I know my way around a car, Doc, the way a cowboy knows his horse."

"Good. I can give you the address of a Mexican in El Paso, big fat fellow called Charlie, can get you a passport that looks better than the real thing, just to cover you in case you get picked up."

"I'm not planning to get picked up."

"I know you're not planning to get a bullet hole in your radiator either, Johnny, but be damn careful."

"That Ford out there is going to be hotter than hell when Harvey gets back to town. I'll need to switch cars."

"I can help you there," Doc said eagerly. "You take me down to the south barn in the woods. I'll surprise you. Here, better take your fifteen thousand back. And take your hardware. You might need both in Mexico."

He carried the case for Dillinger, who carried the machine guns. They went out and got into the Ford. Dillinger drove around to the rear of the farm and took the track down through the trees beside the swamp, following the old man's directions and finally braked to a halt beside an old dilapidated barn in the trees.

They got out. Doc unbarred the double doors, Dillinger helping him, and pulled them back. A white Chevrolet convertible stood there. It looked brand-new.

"And where in the hell did you get that?" Dillinger wanted to know.

"Kid called in here about six months ago named Leo Fettamen. You heard of him?"

"I don't think so."

"Strictly small stuff, but as car-crazy as you claim to be, Johnny. Fettaman robbed a bank in Carlsberg. Bought this and an old ford with the cash. Went into Huntsville in the Ford with a guy who called himself Gruber. They intended to take the bank, come back here, and use the Chevy as their getaway car. The kid had a theory that the more imposing you looked, the less the cops were likely to stop you."

"What happened?"

"Killed in a gun battle with the sheriff and his deputies. Hell, I think half the town put a bullet in them before they were finished. The righteous are terrible in their wrath, Johnny."

"So I've noticed," Dillinger said.

"Obviously I couldn't start riding around in it. That would have caused talk. Seeing's you got eyes for it, Johnny, I'll make a deal with you. It's yours for twelve thousand dollars."

Dillinger smiled and slapped Doc's hand. "Doggone, you got it."

"One thing you'll need from that Ford is the battery. The one in the Chevy couldn't be deader."

Dillinger drove the Ford into the barn beside the Chevrolet, then got a wrench from the tool kit and removed the battery. It was only five minutes' work to substitute it for the battery in the other car, then he slid behind the wheel, pulled the choke, and applied the starter. The Chevrolet's engine started instantly, purred like music.

As he got out, the old man was already transferring his belongings from the Ford. "Anything I've forgotten?"

"You could say that."

Dillinger lifted the rear seat of the Ford, revealing a shotgun and two automatic pistols.

"You going to war, Johnny?" Doc asked.

They stowed the shotgun and pistols along with the rest of the arsenal under the rear seat of the Chevrolet. "That's it," Dillinger said.

The old man shook his head. "No, the Ford, Johnny. That's got to go." He nodded across the track to the swamp. "In there." He slapped the car on the roof with the flat of his hand. "Seems like a waste, but when a man gets too greedy, he can end up on the end of a rope."

Dillinger reached in and released the hand brake, then went round to the rear. The two men got their shoulders down and pushed. The Ford bounced across the track, gathered momentum, and ran away down the slope, plunging into the dark waters below. They stood there watching it disappear, Dillinger lighting a cigarette and offering the old man one. Doc shook his head and put his empty pipe in his mouth, chewing on it until the roof of the Ford had disappeared under the surface.

"That's it."

They went back to the barn and got into the Chevrolet. Dillinger drove back to the farm, braking to a halt at the foot of the porch steps. He started to open his door, but Doc shook his head.

"You've got to get moving, Johnny. Let's cut it now."

"Whatever you say, Doc." Dillinger held out his hand.

Doc said, "I want you to know I'm going to take your advice. I'm going south to the Florida Keys with money in my pants, and it's all thanks to you." He got out of the car and closed the door, leaning down to the window. "I'm going to get some warmth into my old bones before I die, and that's thanks to you as well, Johnny."

Dillinger smiled. "Good luck, Doc." He drove away through the rain.

The old man stood there listening to the Chevrolet's sweet sound fade into the distance. Then he trudged across the muddy yard to the barn and opened the doors. An old Ford truck stood inside. He started it with the handle and drove it across to the front of the farm and went into the house.

When he reappeared, he was carrying a suitcase and the briefcase, no more. He put them into the cab and went back up the steps into the

living room. The hound dog moved restlessly beside him. It was very quiet, with only the rain humming on the roof.

"Quiet, Sam," he said gently. "We're leaving now."

He took out his pipe, filled it methodically from his worn tobacco pouch. Then he picked up the photo of his wife in the silver frame and slipped it into his pocket.

He struck a match on the side of his shoe and put it to the bowl of his pipe, then took the cowl off the oil lamp on the table and touched the match to the wick. The lamp flared up, and he reached forward and very gently turned it on its side. It rolled, coal oil spilling across the table and dripping to the floor, tongues of flame leaping up.

Jack Higgins - Dillinger

Jack Higgins - Dillinger