- Home

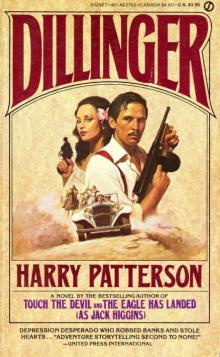

- Dillinger [lit]

Jack Higgins - Dillinger Page 4

Jack Higgins - Dillinger Read online

Page 4

"Why, damn me, Sam," Doc said to the hound. "We appear to have a fire on our hands. Time to leave, I'd say."

He went out to the truck, holding open the door so that the old dog could climb up on the passenger seat. He walked round to the front, swung the crank, then got behind the wheel and moved into gear. As he drove away, he started to sing softly:

John Dillinger was the man for me,

He robbed the Glendale train,

Took from the banks, gave to the poor,

Shan't see his like again.

Behind him, flames burst through the shingle roof, and black smoke billowed into the air. Doc hadn't been happier in years. Then he remembered the man who'd come calling, Leach. The son-of-a-bitch had the whole of the Indiana State Police to catch one man. He hoped Johnny would be across the state line by now. Or real soon.

In his Washington office, J. Edgar Hoover had seven grown men standing around his desk as if they were page boys instead of high-ranking G-men. Hoover's voice was calm, but the men who had worked with him knew that he was furious.

"He phoned me," Hoover said.

Of course they knew already. It was the scuttlebutt of Headquarters.

"He phoned me collect. He said I should tell the President not to close any more banks."

The men standing there kept straight faces because they knew what Hoover's fury would be like if they so much as smiled.

"He's made more headlines than movie stars. I don't want the kids in this country growing up emulating that man. Understand?"

They all nodded.

"The local boobs can't catch him, and when they do, they can't hold onto him. I want John Dillinger taken by the Bureau. Dead or alive."

It was the man standing next to Purvis from Chicago who said, "Any preference?"

Hoover laughed, so they all thought it was okay to laugh too.

Hoover stood up for the first time. "Here's my plan."

Three

In Texas he'd driven with the top of the white convertible down, hoping the breeze would help. Maybe not feeling safe yet was adding to his discomfort. But once he was across the border he felt safe, though the hot sun seemed to bear down on him even more, and he finally pulled over to the side of the dusty road and raised the top to keep the sun off his head. He put the turned down panama hat beside him on the seat to let the sweatband dry out a bit, damn glad he'd bought the panama and thrown the straw hat away. He didn't want to look like an American from a mile away.

With his fingertips he felt the mustache he'd started to grow on the ride down. He glanced in the rear-view mirror. It was coming in black. All he needed was a better suntan.

Above the town the Sierras floated in a purple haze. He bet it was cooler up there, but he had to find a decent hotel, if there was such a place. Across the Plaza Civica that fronted the church, he saw it, the Hotel Balcon, a squat pink building with a crumbling facade. It had been used as a strong point during the Revolution, and the walls were pitted with bullet holes.

He pulled the white Chevrolet up in front of the hotel, aware of the eyes watching him from the park. Maybe from windows up there too. Should he have stuck to a black car like most other people drove, not a white convertible that called attention to himself? He loved the goddamn car and didn't care about anything except that it was now covered in dust and grime. These people sure had lousy roads compared to the States.

Dillinger put on his linen jacket, took the one suitcase. Everything else was safely stowed in the trunk.

He noticed but didn't pay any attention to the old man who sat on the bench in front of the hotel, smoking the stub of a cigarette the way people who can't afford cigarettes do, dragging smoke out of the last half-inch.

As Dillinger passed, the man said, "Hi."

Dillinger stopped. He certainly didn't recognize the old fellow in the crumpled linen suit. He had the face of a man who'd lived hard all his life. A grizzled beard framed his wide mouth.

Dillinger'd been worried about knowing only a few phrases in Spanish, and here was this guy saying, "Hi." Then, "Can you spare two bits?"

Dillinger put his suitcase down. "How'd you know I spoke English?"

"You walk like an American. And I never saw anybody down here drive a job like that." He pointed at the convertible. "Besides," he said with a small-time laugh, "Illinois plates don't grow on cars down here. Two bits, and I'll watch your fancy job while you check in."

"What's it need watching for?"

"The kids around here'll be down on it three seconds after you walk in that front door. I'm cleaned out. Two bits and nobody gets near your car."

Dillinger took out his wallet and extracted a five-dollar bill. "Watch it real good."

The man examined the bill, his face lighting up as if he'd just won a jackpot. "Thank you," he said, stretching the "you" out.

Dillinger was picking up his suitcase again when he heard the man say, "Don't I know you from somewhere, mister? You been in Laredo?"

"No."

"San Antone?"

"No," Dillinger said, and headed up the steps to the hotel entrance.

"Hey, I know who you look like," the old man said. "You look like John Dillinger."

Dillinger looked around to see if anyone was standing within ear shot. The only person close enough to have heard was a fat Mexican woman carrying a basket on her head. No chance she'd know the name even if she'd heard.

"I seen your picture," the man said. "You're him, ain't you?"

Dillinger turned slowly and moved back to face him. "You're mistaken, friend. The name's Jordan-Harry Jordan." He parted his jacket slightly so the old man could see the butt of the Colt pistol holstered under his left arm. "You should be more careful, old-timer. Americans should stick together in a place like this."

The old man said, "I guess I made a mistake. I'm sorry."

"Make them myself every day," Dillinger said and went into the hotel.

On the balcony above the hotel entrance, sitting well back out of the sun, the man who'd rented the best room in the hotel had listened to the exchange with interest. He hadn't heard the actual words, but the new gringo spoke with an authority he liked. He picked up his malacca cane, and, straightening his wide-brimmed hat, he headed down to the lobby, walking with the confidant gait of a man who knew what he wanted.

Dillinger, waiting at the desk for his key, saw the onlooker coming in the mirror. He was tall with good shoulders, his temples brushed with gray, and the broken nose looked out of place in the aquiline face. There was an elegance about him, a touch of the hidalgo in the way he carried himself. He was a breed the revolution had almost destroyed. The proud ones who never gave in. Who had to be broken.

He removed the long cigarillo from his mouth. "Senor Jordan?" he inquired in careful, clipped English.

Dillinger froze. How did the man know the name on his passport? No point in denying it. The hotel clerk knew. The old man in front knew. "Yes," was all Dillinger said.

"Allow me to introduce myself. Don Jose Manuel de Rivera."

Dillinger could tell from the way the hotel clerk nodded to the man that he was a wheel.

"My business can be stated quite briefly, senor," Rivera said. "Perhaps I could accompany you to your room? We could talk as you unpack."

"We can talk right here in the lobby," Dillinger said, gesturing to a glass-topped wicker table with two chairs beside it.

"As you wish," the man called Rivera said.

Just then they both heard the commotion outside, and a cracked voice yelling, "Scram! Vamoose! Get the hell out of here!"

"Excuse me," Dillinger said, and walked quickly to the front entrance, where, as he suspected, the old man was trying to chase away three shirtless teenage Mexican boys, one of whom had already opened the near door of the convertible and was peering into the glove compartment.

With quick strides Dillinger was at the car. He grabbed the kid by his hair and yanked him out of the car, then twisted the kid's

arm behind his back, paying no attention to the stream of Spanish invective. Calmly, Dillinger looked at the other two boys, who were standing on the running board on the other side. Whatever they saw in his eyes, plus the yelping of their friend, sent them dashing down the street.

The old American came around so he could yell at the captive's face. "Ladron! Ladron!"

"What the hell does that mean?" Dillinger asked.

"Thief."

"Tell him I'm going to break his arm so he won't steal anymore."

The old man translated it into rough Spanish. The kid looked frightened.

Then, with one motion, Dillinger flung the kid to the ground, giving him a chance to scamper away.

Dillinger laughed, and only then did he notice that the whole scene had been observed by Senor Rivera from the doorway.

"Bravo, Senor Jordan," Rivera said.

"I apologize for the intermission," Dillinger said, "but I really like that car the way it is."

"Understandable."

The old man, his face a mask of disgrace, was holding out the five-dollar bill Dillinger had given him. "I guess you want this back. I didn't do too good watching your car for you."

"You did fine. If you hadn't yelled, I wouldn't have come out. Just what I wanted." He reached under the front seat of the car and pulled out a big flannel rag. "Here. Why don't you clean the dust off the car while I talk to this gentleman. If you're dusting it, I don't think anybody else will bother it."

"Absolutely, Mr. Jordan," the old man said, taking the rag and hastily pocketing the five-dollar bill again.

Rivera said, "Perhaps now we can talk in your room where it will be quieter, senor?"

Dillinger hesitated and then shrugged. "Why not?"

Dillinger got his suitcase at the front desk, led the way up the broad wooden stairs to the first floor, and unlocked the door at the end of the corridor. The room was like an oven. The fan in the ceiling was not moving. Dillinger yanked the pull chain; nothing happened. He flicked both switches on the wall. One turned on the light. The other did nothing.

"Mexico is not like the United States," Rivera said.

Dillinger moved to open the French windows and nodded toward a table on which stood a pitcher of ice water and several glasses.

"Help yourself. If you don't mind, I'll wash up."

When Dillinger took his jacket off, Rivera noticed with interest the under-arm holster and gun. No wonder the man could act with such authority. So much the better!

Dillinger put the holster down within easy reach. This Rivera looked rich. Dillinger trusted rich people less than poor people.

He stripped to the waist, poured lukewarm water from a pitcher into the basin on the wash-stand in one corner, and sluiced his head and shoulders.

Rivera said, "If you have not been to Mexico before, I recommend you order bottled water, Senor. American stomachs do not like our water."

Dillinger nodded his thanks. Rivera sat down in a wicker chair by the table, and Dillinger walked to the window, toweling his damp hair. A steam whistle blasted once, the sound echoing back from the mountains across the flat roofs, and a wisp of smoke drifted lazily into the sky from the station.

Rivera put down his glass and said, "I'd like to offer you a job, Senor Jordan."

"What kind of a job?" Dillinger was amused. This guy sure didn't know who he was.

"I've reopened an old gold mine near my hacienda at Hermosa. That's a small town in the northern foothills of the Sierra Madre, toward the American border. Hermosa and the area around it is rough country. The peasants are animals, and the Indians who work the mines...." He shrugged. "But you will find this out for yourself. What I need is a man of authority, who will work with me for six months or a year. Keep discipline. You know what I mean?"

This guy was fascinating, Dillinger thought. "Who keeps discipline for you now, Mr. Rivera?"

"Ah," Rivera said. "I had a good man, also an American, very tall, very strong. He didn't want to go back to the States, the police bothered him there, and so he had an accident, and now I have to replace him. I hope with you."

"In one sentence," Dillinger said, "not a chance."

"You have not heard my terms, senor. Two thousand dollars in gold for six months, five thousand dollars in gold for a year."

Dillinger was really tempted to tell this fancy jerk that he'd made that much in five minutes by vaulting over a counter and emptying a teller's drawer.

"En oh," Dillinger said. "That spells no. But how would you like to work for me while I am in Mexico? You could be my guide. I'll pay you a thousand dollars for a month, how's that?"

Anger blazed in Rivera's dark eyes. The jagged white scar, bisecting his left cheek that Dillinger hadn't paid attention to before, seemed to stand out suddenly against the brown skin. Rivera took a cigarillo from his breast pocket and lit it. When he looked up, he had control again.

"I know you did not mean to insult me, Senor. You do not know the ways of Mexico." He took a slow puff. "I usually get what I want, Senor Jordan. We have a saying: A man must be prepared to pay for past sins. I will pay you double what I paid the other American if you return to Hermosa with me. My final offer."

"Thanks, but no thanks," Dillinger said gently. "I'm really here on a kind of vacation."

He was aware of the sweat trickling from his armpits, soaking into his shirt. He poured himself a glass of ice water, then remembered Rivera's warning about the water.

Rivera said calmly, "Your final word?"

"Yes. Sorry we can't do business."

Rivera walked to the door and opened it. "So am I, Senor Jordan. So am I."

Rivera closed the door behind him, descended the wide wooden stairs to the lobby, and went outside. He found the old man who was guarding Dillinger's convertible sitting on the bench, a small bottle of tequila in hand. So, he'd spent some of the money already.

"Hello, Fallon, I thought I recognized you. Having a difficult time of it lately?"

The old man looked at him sourly. "You should know, Mr. Rivera!"

"You needed a lesson, my friend," Rivera said, "but that's history now. You can come back and work for me at Hermosa any time you like."

"That's not work, Mr. Rivera. It's slavery."

"As you choose. Who is this Senor Jordan?"

"Jordan?" The old man stared at him blankly. "I don't know any Jordan."

"The one you were talking to. He owns the automobile. Who is he? What's his game?"

"I ain't telling you a damn thing" Fallon said.

Rivera shrugged and walked along the terrace. Two men were sitting at the end table eating frijoles, a bottle of wine between them. One was a large, placid Indian with an impassive face, great rolls of fat bursting the seams of his jacket. The other, a small, wiry man in a tan gabardine suit, his sallow face badly marked from smallpox, got to his feet hurriedly, wiping his mouth. "Don Jose."

"Ah, my good friend, Sergeant Hernandez." Rivera turned and glanced toward Fallon. "I wonder if you might consider doing me a great favor?"

Hernandez nodded eagerly. "At your orders, as always, senor."

Twenty minutes later, Fallon surfaced with a shock as a bucket of water came hurling onto his face. One side of his face hurt from his eye to his jaw. He was lying in the corner of a police cell. The big Indian who stood over him must have hit or kicked him. Fallon's side hurt as much as his face. Sergeant Hernandez sat on the bunk. Fallon recognized him instantly and went cold.

"What is this? What have I done?"

"You are a stupid man," Hernandez told him.

"I'm an American. You have no right to put me in here," Fallon said.

"If you don't like our ways, why don't you go back? You want me to escort you to the border and turn you over to your Federalistas?"

Fallon shook his head.

"You are here because to go back there you have to spend fifteen years in jail, is that not so?"

The massive Indian moved within kicking d

istance of Fallon.

"You see," Hernandez said, "he only knows one thing. Kicking."

Fallon rolled away from the Indian, which brought him closer to Hernandez.

Hernandez leaned down and whispered to Fallon, "I think you will now stop being stupid. Now I think you may even try to be sensible? Is this not so?"

Jack Higgins - Dillinger

Jack Higgins - Dillinger